"Nashville Obsolete" Finds Dave Rawlings Opining On Present Circumstances by Lee Zimmerman 9/15/15 from No Depression

- Posted by Brian1964Smith

- November 15, 2015 9:38 PM PST

- 0 comments

- 1,731 views

You might say Dave Rawlings is an opinionated guy. That’s immediately evident the first time you speak to him at any great length. He freely answers whatever questions an inquiring journalist might pose. If he’s really interested in the topic at hand, he’ll go on at great length to share his perspective. Yet, there’s a certain irony in that. As an artist, he’s often taken on a support role, particularly with his longtime musical collaborator Gillian Welch, for whom he writes, produces, and plays guitar on albums released under her name alone. The sole time he put his own name on the banner was with the first Dave Rawlings Machine album, A Friend of a Friend, in 2009. Even that outing found Rawlings sharing the spotlight. It was a communal affair, featuring various friends and fellow travellers, that positioned him at the helm of a project, but hardly alone.

Six years later comes Nashville Obsolete, the second Dave Rawlings Machine album, releasing this week. This time, Rawlings has cut the cast down considerably to just him, Welch, the Punch Brothers’ Paul Kowert on bass, amd Willie Watson on vocals and guitar. Guests Brittany Haas and Jordan Tice -- who play with Kowert as the trio Haas Kowert Tice -- fill in on fiddle and mandolin, respectively.

Only seven songs long, Nashville Obsolete totes a rudimentary sound in many ways. It's very arcane and archival-sounding with the only real embellishment coming in the way of occasional strings that complement the arrangements, but never overwhelm them. In some ways, it recalls Neil Young’s Tonight’s the Night or Bob Dylan’s Blonde on Blonde in its ominous overtones and barren soundscapes. Not surprisingly, Rawlings referred to both albums in our recent conversation.

Like the traditional music Rawlings often emulates, the album finds every song relaying a story of some sort. But as Rawlings is prone to do, he prefers to leave the interpretations to others. Therein lies the contradiction: an opinionated artist with a determination to make music that he can enjoy, while leaving his listeners to derive their own conclusions.

Following the lengthy interview I had with Rawlings for this year's No Depression print magazine -- at which time Nashville Obsolete was not quite complete -- I dove into this conversation enthusiastically and asked Rawlings to comment on his modus operandi. While I didn’t always get the answers I was looking for, I did get the interesting conversation I anticipated.

Lee Zimmerman: It’s been a couple of months since we last spoke. So how are you?

Dave Rawlings: We did just a little mini tour and I got bit by some sort of poisonous spider, so that was a strange week. But I’m pretty much walking around and feeling better now.

Your new album is ready to release. When we talked [for the print magazine], it was in the sort of prenatal stage.

It’s finished. I can say that.

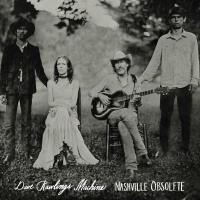

The cover is very rustic looking. It befits the tone of the music. Very traditional and homespun. It looks like a Matthew Brady photo, circa the Civil War.

It’s actually a tintype. Metal on metal. It’s a very meticulous process. My favorite comment on the cover was from some kid I saw in a bar in Nashville right when we made the announcement. He must have seen it on the website, and he said, “Mr. Rawlings, man I really like that cover. Man, that’s some Civil War shit right there!” Everyone looks like a criminal. [laughs]

It complements the music so well, because the music sounds so rustic. It replicates a very traditional template. Was that the intention?

I don’t know. We just play things the way we like to hear them and I guess those are sounds that we enjoy, so I guess it makes sense that they would turn up in our music. There’s a lot less intention in what we do than that which appears. There’s always just one driving factor: the impulse that you yourself can enjoy [making the music] while you’re doing it. That’s a tricky enough proposition. If you put any other stipulations on it, if you say to yourself, I’m going to make something I love, but I’m going to do it this way or that way ... I find those stipulations fall by the wayside faster than you can blink. [laughs]

So you’re saying there was no overarching concept that was mapped out ahead of time?

I think as a writer or producer, you can guide things in the most gentle way. If you notice that certain themes pop up, you can try to nourish those themes. You can develop them a little more. And I think that’s what we did that with the material on this record.

Sonically, my intention was just to make this a trio record with Gillian and I and Paul on bass, and I wanted that in order to force myself to play some guitar solos. On the other Machine record, with a big ensemble cast, I didn’t end up playing that much guitar. Some people were disappointed with that, and I know I was disappointed with that. It’s like, Hey, I’m making a record and I shouldn’t neglect my guitar. Even so, the extra attention it takes to be the front person and do the singing means I don’t get to play as much guitar as I would on a Gillian record. It’s just a fact of life, because my attention is going to be naturally divided. Then again, there are different colors on the record, like adding Brittany on fiddle and using Willie Watson on vocals. These are all things we like the sound of, so it’s natural to emphasize them. I like the spontaneity we got, the interplay between our instruments. I’d play something on guitar and Brittany would respond on fiddle, and vice versa.

This album is quite different from the first Machine album.

I agree. This is more of an actual record. We kind of made that first one to get our sea legs back, because we hadn’t made a record for a long time. The songs were from various time periods, and we wrote a few while we were recording it, and it all turned out okay, but in some weird way, that album felt like a greatest hits [album] for a band that never had made any records before. It seems like it was a compilation of five records that could have come out before that. But this is an actual album. I think there is a story that’s told by the album as a whole, in addition to the stories told by each song.

Here again, it has been some time since your last album with Gillian.

That’s true, but we don’t live in that world where one puts out an album, goes out and does a dozen shows, and then is forced by the record company to go back and start recording again. The world has basically declared the album a worthless art form, so people have to go out on the road because they have to make a living. I produced a couple of albums in the interim as well, so I’ve been plenty busy. Once we get back from being on the road, a certain amount of time had passed. People still live in this fantasy world where albums can come out every year. [laughs]

This is clearly a Machine album, but there doesn’t seem to be any sort of distinctive transition from what you were doing with the Machine six years ago. It’s almost like a fresh beginning, with this rustic tone to it.

I hear what you’re saying. It felt like a first record to me. It was the first time we took a body of work that we wrote and applied it to the Machine or to me singing. We didn’t know what we would get. It does feel pretty cohesive, so it is nice that way. I’m interested that you hear it that way, because I never know how these things are going to hit anybody. We thought a lot of these songs were very noncommercial when we were working on them.

One of the first things we finished was “The Trip,” this giant sprawling thing. And there were extra verses to that which didn’t end up on the record. We were thinking, what value does this have? Who wants to hear this? [laughs] Well, in the end, we wanted to hear it. We kept returning to it. We enjoyed it, so we recorded it.

We did a few little pop up shows where we debuted this material before we recorded it and people seemed to really enjoy it. So that was a nice little boost of confidence for us, going into the studio and recording these songs. We played them four or five times for people live, and though they had never heard them before. They responded very well to them.

There is an air of familiarity to the music. The songs have a kind of timeless quality. They’re very pure.

Interesting observation. Great. I’m certainly a fan of music that isn’t too far from this. I don’t have the same relationship to my music that I have to the music that I love and grew up on, or even brand new music that I listen to. If it comes from someone else, it’s certainly a different story. But I do think [we did] a decent job of taking elements of things we love and putting them into our own music. To hear you say that makes me think we hit the mark a few times.

That archival sound that’s imbued in the music is an obvious element.

Yeah, we are fond of those themes -- the way that folk music is able to talk about life in a slightly broader way than other genres. Anything is fair game. The blues is in there. The murder ballad is in there. The love song is in there too. If you think of Dylan’s beautiful expansion of the folk tradition, where he pulled in part of Woody Guthrie’s wryness and Allen Ginsburg’s kaleidoscopic vision ... all of that stuff has turned into this language for us. It’s fun to try to express yourself within that language and try to add to it. To take the things you’re feeling about life, and express them in these terms, and [in] that beautiful language.

Your previous comments to the contrary, it sounds like there’s a measure of deliberation in what you just said. That there was an intention to express things in a certain way.

But I don’t know how to express things in any other way. This is the language that we use. I always think, with music, it’s difficult to discuss it to begin with. I’m an analytical guy. I can analyze anything.

Critics and music writers love that exercise, however.

The thing is, though, that analysis doesn’t always connect to the art of creation. You think of something and you don’t know why you thought of it, so you immediately start drawing lines. It could be a lyric or a musical phrase, and all of a sudden I start feeling like a rock climber who’s rappelling himself off the mountain from 50 different directions. Like this is connected to this, or this is connected to that. The truth is, I don’t think of it that way. I’d be in a completely different conversation if the way we made art was to say, "We need this or we need that."

I’m not saying it doesn’t happen. It’s really fun when you have to use a different part of your brain -- the creative part -- to add to something creative that you’ve done. It’s a great pleasure, but it’s not the norm. So I can talk about the language we work in with Gillian and our personal mythology, but it’s like asking James Joyce why he’s obsessed with certain themes in his books. I’m sure he can tell you why he’s interested in them, but at the deepest and truest level, none of us have any idea.

Isn’t there an ultimate goal in the creative process though? Even if it’s that "We’re going to put out an album that just sounds great"?

I think the ultimate goal for me is to make something that other people can enjoy, the way I enjoy the music that I enjoy the most. I think of the incredible pleasure I get from listening to this record or that record. [Like] a Chet Baker trumpet solo, something I can really connect to that changed my life. The highest goal is to create that experience for someone else and hopefully make a living while you do it.

There’s no way that you can convince me that my first listening to an album like Tonight’s the Night, or what happened to me from age 14 to 18 when I discovered all of Bob Dylan’s music, weren’t the most important things in my life, in terms of what shaped me as a person. I look at those things in the highest esteem. I think that’s true of any artist. You can talk to a visual artist about how they looked at a particular painting and how it changed their vision of the entire world. The desire to get closer to that and create something like that for yourself is a very natural human desire.

For a long time before I played an instrument, I didn’t think that was something you could create. I thought it was magic. And then the moment I had a guitar, I realized someone worked this machine and actually made that! [laughs] That changed my life. When you talk about this record and where it succeeds for you or even where it fails for you, those things are interesting, but they are all secondary to some degree. We could talk about the way the string instruments came out, because I’ve never done string arrangements and I had five days to learn how, and then write them and then go down and record them, and I’m happy about that. That was a new additive, a new tool that we had. It’s exciting, it’s fun, and I like the way they colored the record. But I don’t know what else to say about it. That’s maybe the only specific part of this record that I can quantify.

What can we read into the title, Nashville Obsolete?

You can read into it in about ten different ways, so I don’t know how you hear it.

Maybe as a rebellious statement about how Nashville is today, versus the old Nashville?

That’s five percent of that title for us. A lot of it refers to the fact that music as a commodity is obsolete. We work on analog tape, which is an obsolete format. We play obsolete instruments, mostly. We use obsolete microphones. We record in an actual recording studio which is an obsolete business. All of these things sort of touched that. Nashville has changed a lot since we moved here. But I’m not here to judge whether that’s good, bad, or indifferent. Change is change. You could also look at Gillian and I and say, “There goes a Nashville obsolete.” [laughs] We’ve been there a long time. We’re not part of the new guard. We’re part of the old guard now. I think it’s connected to that.

So that’s a couple of the different ways it can be interpreted. Give us a few of the others things you had in mind.

Well, let’s see. Initially the phrase came about because we manufactured these little springs, these little retaining clips that were for a reverb, echo device. Once you’ve broken the clips, you can’t find them anymore, so we remanufactured them and we always joked that we should start a little business called Nashville Obsolete. [We'd] have it be mail-order only, and we’d send out these old fashioned catalogs that would say, “If you don’t need it, we’ve got it.” Maybe we’d sell typewriter ribbons or floppy discs. There are a thousand things that are just gone from the world and we laugh because we need these things on a daily basis in our world.

Working in the music industry and being an old-time musician, we’re just endlessly trying to recreate something that doesn’t exist anymore. That’s where the phrase came from. So after we made the record, it crossed my mind that it was a good title for the record, because all of the things we do as writers and performers that no longer exist. It’s a little bit of a celebration of that and just an acknowledgement of that at the same time.

I like a title that you can immediately remember and you can immediately refer to without feeling uncomfortable. Titles have a job to do. Why is Blonde on Blonde called Blonde on Blonde? I couldn’t tell you. I guess that cover photo is a little tan looking, but who knows? It connects to the music in some metaphysical way. So maybe I’m making that connection. But I know that I enjoy calling that record Blonde on Blonde and I hope people enjoy calling this record Nashville Obsolete. That’s really all I’m looking for. A title is just a title.

Is that all there is to it?

I think the word “obsolete” also goes well with the word “machine,” and I think the word “Nashville” works for us as people who live there and have done a lot of our work there over the years. So there’s a couple of other connections that it just naturally has.

It sounds a little more insurgent than that.

Well, there’s a little of that in there, but I’m not going to be the one to wave that banner, because I have too much respect for Nashville as a city to make music [in]. I’m not deluded as to the importance of a Dave Rawlings Machine record. I know what we’re making and I’m proud of it, but I’m not insane. [laughs]

If Taylor Swift called her next record Nashville Obsolete, that would mean something entirely different.

Comments